Brexit vote: British Parliament overwhelmingly rejects Theresa May’s plan, diminishing chance of withdrawal on March 29

After Parliament rejected the latest Brexit deal March 12, British Prime Minister Theresa May expressed her regrets and outlined the course of action ahead. (Reuters)

By William Booth and

Karla AdamMarch 12 at 6:54 PM

LONDON — Three years after Britain voted to leave the European Union, lawmakers have failed to agree on how to do it.

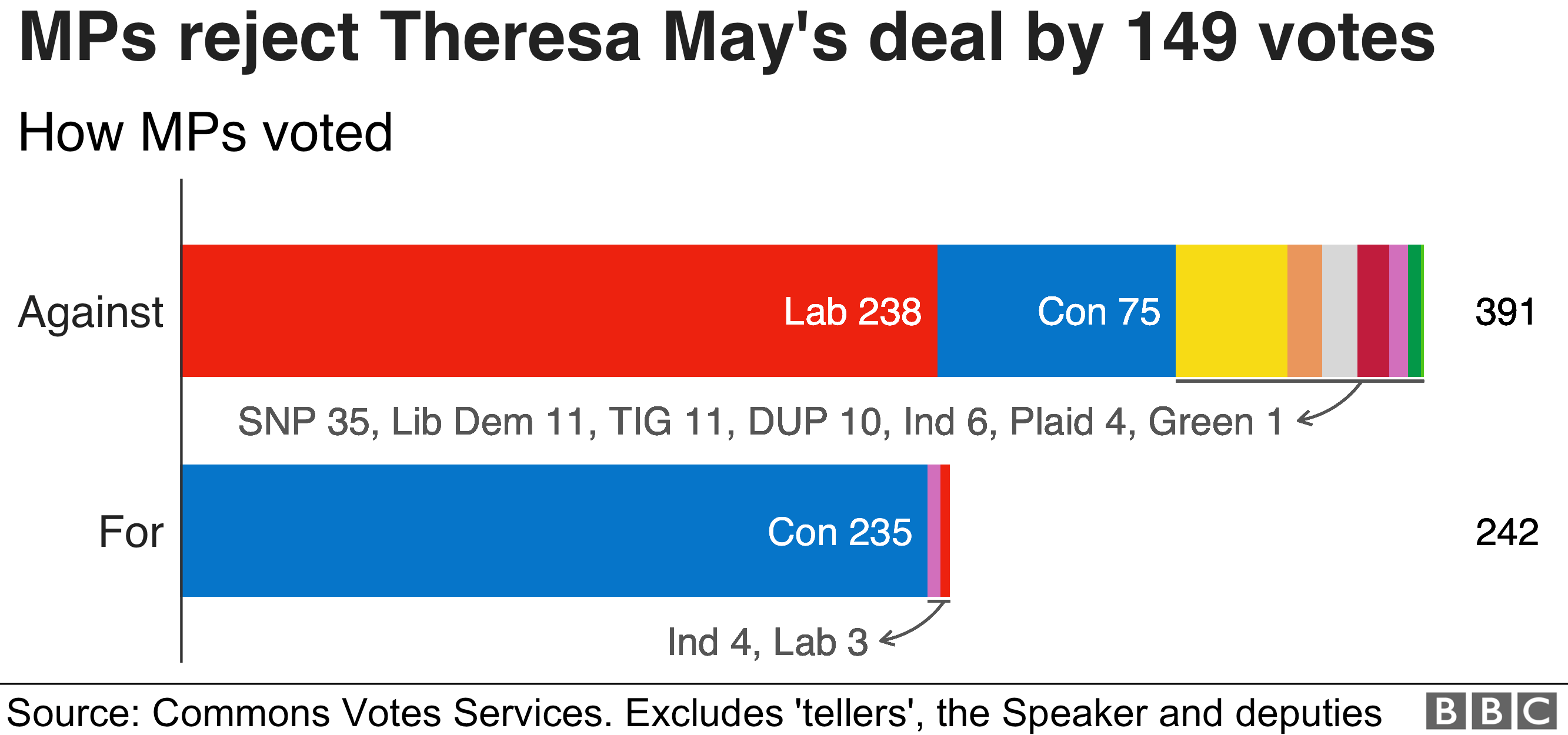

Parliament rejected Prime Minister Theresa May’s revised Brexit deal Tuesday in a vote of 391 to 242, the second time she has suffered such an overwhelming defeat.

Last-minute negotiations with E.U. leaders were not enough to secure the support of hard-liners in the prime minister’s Conservative Party — 75 Tories voted against their leader.

The loss raises questions not only about May’s authority, but also about how Britain will exit the trading bloc. With just over two weeks before the Brexit deadline, the options are narrowing.

Parliament will vote Wednesday on whether to leave the European Union on schedule, on March 29, without a deal — a scenario that could create economic havoc for Britain and, to lesser degree, Europe.

Boris Johnson, the former foreign secretary and a leading Brexiteer, argued in favor of a no-deal Brexit on Tuesday. While acknowledging “that is in the short term the more difficult road,” he said, “in the end, it’s the only safe route out of the abyss and the only safe path to self-respect.”

But there doesn’t seem to be the stomach in Parliament for it. More likely, lawmakers will push to keep trying for a managed withdrawal. In that case, they will vote Thursday on whether to request a delay from leaders of the European Union’s remaining 27 member states.

European leaders have suggested they would grant a delay but have warned their patience is not infinite.

Europe “will expect a credible justification for a possible extension and its duration,” said a spokesman for European Council President Donald Tusk. “The smooth functioning of the E.U. institutions will need to be ensured.”

The top E.U. negotiator Michel Barnier, showing his frustration, tweeted that with the British Parliament paralyzed, “our ‘no-deal’ preparations are now more important than ever.”

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker told reporters after meeting with May in Strasbourg, France, on Monday night that the union was not willing to reopen talks. “There will be no new negotiations,” he said.

May also seemed to have reached her limit on talks. Her voice was nearly gone on Tuesday — a spokesman blamed a bad cold. “I profoundly regret the decision that this House has taken tonight,” May conceded.

May said Conservative lawmakers would not be whipped to vote one way or another on whether to leave with or without a deal — that Wednesday would be a “free vote,” meaning lawmakers don’t have to adhere to party lines.

She noted that while leaving without a deal is the default legal position, she and her government would prefer “an orderly Brexit.”

“Voting against leaving without a deal and for an extension does not solve the problems we face,” she added. “The E.U. will want to know what use we mean to make of such an extension, and this House will have to answer that question.”

“Does it wish to revoke Article 50?” May asked the House of Commons, meaning no Brexit? “Does it want to hold a second referendum? Does it want to leave with a deal but not this deal?”

May has said previously that if an extension beyond March 29 were necessary, it would be granted only once by the European Union, and that it shouldn’t go beyond the end of June.

Anti-Brexit lawmakers hope that if Britain’s departure is delayed, momentum will build for a second referendum — a do-over — to ask voters whether they really want to leave.

Although the opposition Labour Party has endorsed a second referendum, there does not appear to be majority support for it in Parliament.

“There isn’t actually evidence that the British people have changed their minds,” May said to lawmakers Tuesday. “And where would it end? So what? So you have another referendum, and there’s a different result, and then everybody says, well, let’s actually have a third one.”

Pro-Brexit demonstrators in London protest in the rain ahead of Parliament’s vote. (Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Speculation was rife about what would happen to May now.

Her supporters say the prime minister crafted a sensible compromise, the best that the European Union is going to offer. It would get Britain out of the bloc, control borders and end free movement of E.U. citizens into Britain — while protecting the Good Friday accords that brought peace to Northern Ireland.

But the prime minister’s strategy has been resisted by lawmakers who want to reverse Brexit and by those who want to leave with no deal and make a clear break.

Some want a softer Brexit, others a harder Brexit. The Northern Irish unionists who prop up May’s government want to remain close to the United Kingdom. The Scottish nationalists want to remain close to Europe.

May told lawmakers they should not blame the European Union for the impasse, only themselves.

Many in the House of Commons, though, blame May, who has a reputation for being determined but lacking oratory prowess and vision.

Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform, predicted Parliament would take greater control of the Brexit process and push for a softer withdrawal. That could split the Conservative Party and produce a renewed attempt to oust May from Downing Street, he said.

“In such circumstances, it’s possible that the right wing of her party would try and bring her down in the hope of installing a different Tory leader,” he said.

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour Party, said May had “run down the clock” and her deal was “clearly dead.”

“It’s time that we have a general election, and the people can choose who their government should be,” he said.

Charles Walker, a Conservative Party politician, told the BBC that if May’s deal was rejected, “as sure as night follows day, there will be a general election within a matter of days or weeks.”

Ahead of Tuesday’s vote, May told Parliament that she had secured the “legally binding” assurances they sought from the European Union that would guarantee Britain won’t be “indefinitely” tied to European rules and regulations, even if the sides cannot agree in the future on how else to keep the border on the island of Ireland free and open.

But an opinion from Attorney General Geoffrey Cox proved devastating.

Cox said May’s tweaked deal did “reduce the risk that the United Kingdom could be indefinitely and involuntarily detained within the protocol’s provisions,” but he warned that “the legal risk remains unchanged.” Cox said Britain would have “no internationally lawful means of exiting the protocol’s arrangements, save by agreement” with the Europeans.

Three terms you need to know to understand Brexit

With the March 29 deadline for Britain to leave the European Union approaching, here are explanations of three terms that help make clear what's at stake. (Sarah Parnass, William Neff, Jayne Orenstein, Thomas LeGro/The Washington Post)

Cox’s assessment helped influence Brexit hard-liners and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to vote against the deal.

The withdrawal agreement, which will still serve as the foundation of any future deal, is only about the terms of departure and does not include what the future relationship between Britain and the E.U. will look like. It sets out the $50 billion divorce settlement that Britain will pay; it allows for a two-year transition period, when things will remain essentially as they are now in terms of trade, migration, security and travel; and it seeks a guarantee to preserve the free and open border on the island of Ireland.

It is that guarantee — the Irish backstop — that is at the heart of the impasse. Many British lawmakers fear that it would limit their country’s sovereignty, requiring them to continue to abide by European rules and regulations on customs and trade forever, without having any say. Some have hoped for a sunset clause, or a provision allowing Britain to unilaterally terminate the backstop.

E.U. leaders on Monday offered fresh pledges that they would seek all possible ways to avoid invoking the politically toxic plan. They wanted to give May a fig leaf, allowing her to say she had received concessions and win over wavering British lawmakers ahead of Tuesday’s vote. But the assurances were framed as the E.U.’s final offer.

In Brussels and across Europe, the mood was black following the vote, with many leaders warning publicly that they were stepping up their preparations for a chaotic, no-deal Brexit and some warning privately that they were completely serious — despite British assumptions that an extension to the departure deadline will be granted more or less automatically if they ask for one.

“Deeply saddened by the outcome of the #Brexit vote this evening,” Danish Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen tweeted. “Despite clear EU-assurances on the backstop, we now face a chaotic #NoDeal #Brexit scenario. And time is almost up.”

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte said on Twitter that he wanted “a credible and convincing justification” for why an extension should be granted, if Britain asks for one.

“Very much depends on the U.K. prime minister and her proposal for what she wants to achieve during an extension,” said a senior E.U. diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss internal thinking about Brexit planning.

The diplomat said that E.U. leaders do not currently believe that the departure could be extended beyond May 24 unless Britain holds elections for European Parliament that are scheduled for that day — a move that is likely to be unpopular on both sides. A British vote would be “quite an entertainment,” the diplomat said, calling the situation in London “a mess of historic proportion.”

A discarded anti-Brexit sign outside Parliament. (Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Michael Birnbaum and Quentin Aries in Brussels contributed to this report.